Zaynab Issa Took Inspiration

“If you are the child of immigrants, you’re very familiar with the phrase “third culture”—it’s the only way you can make sense of your identity. Calling myself just “American” or “Khoja,” “Indian” or “East African” doesn’t feel right. But I find peace in the amalgamation of it all—a “Third Culture kid” with roots everywhere.”

—Zaynab Issa

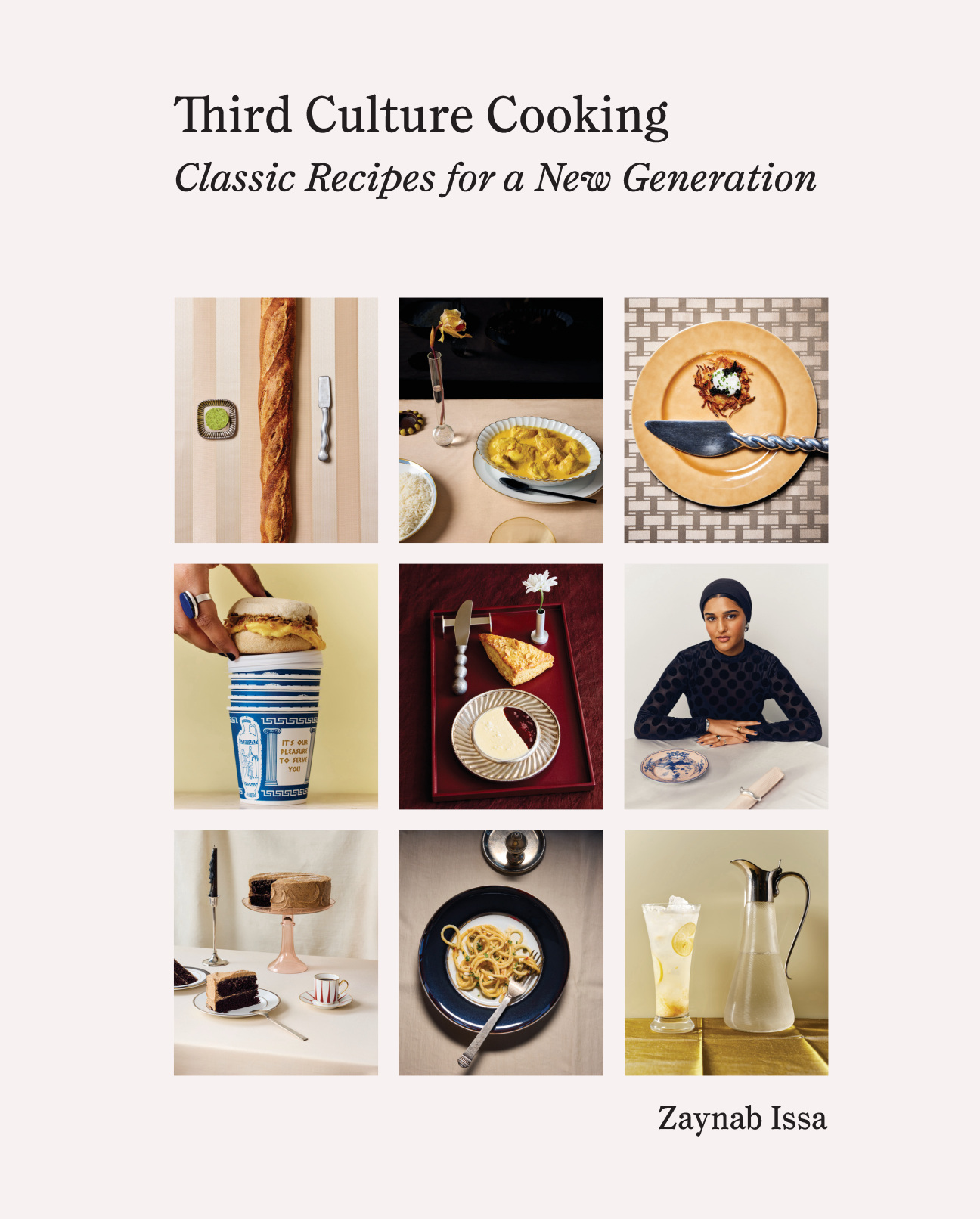

Third Culture, the title of Zaynab Issa’s debut cookbook, hooked me immediately. I felt like I knew exactly what I would find inside, (the sign of a great title) and I couldn’t wait to sink in and read every page. I expected I would find a portrait of Zaynab reflected back—and one of so many others, including myself.

When I met with the 26-year-old recipe developer and writer to discuss Third Culture, we spoke not only of the delicious, approachable, and deeply personal recipes it features—Zaynab’s Baklava Granola and her mother’s pilau among them—but also of the maternal lineages that shaped us, teaching us to make connections across generations, most often through food.

Zaynab’s approach to recipes is one of empowerment—to find your own “third culture” and cook from a place that is unique to you. Without fail, the best food, recipes, and stories are ones that touch us all. It’s also a call to action: “I want to encourage people to create their own third-culture recipe books through mine,” she says. Below, we discuss our shared reverence for culinary fusion, the women who inspire our recipes, and Zaynab Issa Took Inspiration commitment to honoring origins—her family’s, and her own.

Mina Stone: Can you tell us about yourself and your work?

Zaynab Issa: I am the child of East African and Indian immigrants. I’m ethnically Khoja, which is an ethnic group with geographical ties to India, Islam, and the Middle East. I am also East African and I grew up in suburban New Jersey. My grandmother lived with us, and she brought the traditional Khoja heritage and Gujarati influence into our cooking. That’s the South Asian in me. My mom spent some time growing up in London, and my dad did medical school in India before they both moved to Buffalo, New York. They had four kids—I’m the third. I was surrounded by an ever-present, nurturing system. When you have so many people in the house, food is central.

I spend a good deal of the cookbook talking about the influence that the women in my life have had on me. Most of my work is inspired by their untold stories. When I first self-published a zine out of college, Let’s Eat, I reached out to my grandma and my mom to teach me how to record the recipes I had grown up with; we developed them together.

[At first,] it seemed like no one was really interested—then all of a sudden people were. With this book, I wanted to call out each woman who has influenced me, using the headnote to tell their story in addition to sharing their recipe. That’s one aspect of the book I’m most proud of.Stone: When I ask you to talk about yourself and your work, you’re tracing the history of your family and the people who influence you.

Issa: I can’t talk about myself without talking about them. If I’m being truly honest, I became interested in food through the experience of women cooking. I appreciate the effort, whether it was a choice that they were consciously making or one that kind of happened to them.

Stone: It’s a good segue into talking about the title of your book.

Issa: If you are the child of immigrants, you’re very familiar with the phrase “third culture”—it’s the only way you can make sense of your identity. Calling myself just “American” or “Khoja,” “Indian” or “East African” doesn’t feel right. But I find peace in the amalgamation of it all—a “Third Culture kid” with roots everywhere. What I wanted to do with the title is reframe fusion food because I feel like it’s looked down upon.

With context, I think the title is really beautiful. It’s representative of real experience that’s also reflected in the recipes themselves. For example, granola is not something that my mom would ever feed us for breakfast, but parfaits were everywhere and I loved them. When I think about oats, nuts, and cinnamon, I think about my grandma’s baklava. Baklava granola is technically “fusion,” but there’s a story for how it was created. Third-culture cooking is the perfect way to think about a lot of the food that we love. You’re doing a disservice by calling it one cuisine or the other. It’s this “third thing”—making sure we’re not erasing the roots is important.

Stone: It’s respecting everything as it exists in the past and present. If I’m cooking Greek food and using what’s local and available in New York City, it’s going to be different than if I were to fly in a vegetable that I can only get in Greece.

Issa: Exactly—using canned coconut milk is not the same as blending up a whole coconut in East Africa. I’m not going to pretend like it is.

Stone: Is your granola recipe in your book?

Issa: Yes, it’s made with ghee, cinnamon, and orange zest. I do pistachios and walnuts because that’s the mix my grandma uses. Wherever I can, I try to include suggested swaps for any ingredients. I want to encourage people to create their own third-culture recipe book through mine.

Stone: What is the recipe that’s closest to your heart in the cookbook?

Issa: My mom’s pilau, which is a Swahili rice dish made with cumin seeds, beef stock, and goat meat. It’s something she’s always made. Growing up, I didn’t like it. Now, it’s my number one request when I visit her. I like to eat it with pickled onions and salted yogurt. There’s so much history in that recipe, beyond the fact that it’s really good. It’s representative of my relationship with my mom—it’s taken its course.

Stone: Describe the process of making the book.

Issa: I feel very precious about the process. I don’t know if I should admit this, but I really miss writing it—doing the research, cooking all the time. It was very fulfilling to be working on something consistently that was so meaningful. I also think this book is memoir-esque, and so that added another layer.

Stone: Can you draw a parallel between your relationship to cooking and to people? I ask you this because I read that you started to cook as a way to unite people.

Issa: My mind goes to the generational connection. I think about how I interact with older people, which isn’t necessarily a natural skill. When I speak with older women, food is something to bond over. Food unites people generally at the table, but it also can create those cross-generational connections, which I’m starting to value even more as I get older. That’s cultural preservation at the end of the day.

Stone: As you mentioned, [older generations of women] didn’t necessarily have a choice. Women cooking is so ingrained in so many cultures. In Greek culture, there is this word for homemaker that insinuates so much more—it’s almost like being “an artist of the home” or “the caretaker of the home.” I don’t think that respect exists, even linguistically, in our culture.

Issa: It’s funny, the only parallel I can think of is a lifestyle influencer. This is something I think about all the time—Why am I celebrated for doing the same thing they were doing‚ especially when they were probably doing it better? So many of the women [in my life] had beautiful homes, they had that attention to detail. They probably were [influencers] within their communities. Now there’s so much more appreciation and gratitude, and that’s just not how their world worked.

Stone: Well, now they have you.

Issa: I know, they all seem very happy and excited, which is nice. I’m so glad I was able to name them all. My grandma has two [recipes] in there, so she’s thrilled. She’s the only one with two.

Stone: What’s a kitchen etiquette rule you live by?

Issa: Clean as you go.

Stone: What’s one recipe that you’re returning to again and again these days?

Issa: I’m making my A Different Date Shake a lot right now. It’s fast, flavorful, and most importantly, caffeinated.

Stone: What would be your last meal?

Issa: My mom’s pilau. Rishma’s Pilau on page 143.

Stone: What’s next for you?

Issa: Cookbook tour! I’ll be all over the place this Spring.